“We should strive to be good ancestors”

What do nuclear wars, human-made pandemics and internet cables have to do with the builders of medieval cathedrals? Interview with futurologist Lord Martin Rees from the University of Cambridge.

Interview: Sebastian Sele

The flap of a butterfly’s wings can be enough to upset the world’s balance. This “butterfly effect” is at the core of chaos theory. A certain sequence of seemingly small decisions can indeed have an enormous, even existential impact. Researchers at the Centre of the Study of Existential Risk (CSER) at the University of Cambridge are investigating existential risks with the potential to wipe us out as a species.

Martin Rees is one of three co-founders of the CSER. The former Professor of Cosmology and Astrophysics at Cambridge witnessed how the inventors of the atomic bomb opposed the use of their own invention. And he realised: a new generation must succeed them to continue this ethical endeavour. Rees, 83, a member of the House of Lords, former President of the Royal Society and one of the most highly recognised scientists in the world, has dedicated himself to the fight for good.

Lord Rees, you co-founded and continue to work with the Centre for the Study of Existential Risk. Why?

As a professor in space science, astronomy and physics, I gained two perspectives: first, a sense of the cosmic timescale. We humans are not the pinnacle of the cosmos – the sun is not even halfway through its lifetime, so we may not even be halfway through our own evolution towards complexity and consciousness. Second, the recognition that we are the first species with the power to alter the entire planet. I worry about the dark side of powerful technologies. And many other scientists share my concern.

What does CSER’s work look like in practice?

Since 2012, we have been looking at extreme risks, from artificial intelligence and biotechnology to climate change and food security. Researchers from disciplines as diverse as biology and philosophy come together to better understand these existential risks and, in doing so, to help make the world a better place.

So CSER is not just about research?

No, we also advise governments and international organisations. When we began, many dismissed our work as alarmist. We were written off as doomsayers. But since Covid, no one says that anymore – and that was a virus with a fatality rate of less than one per cent. Imagine a virus with a 70 per cent fatality rate.

These apocalyptic scenarios sound rather like science fiction. How can you guarantee that you are not just stirring panic with pseudoscience?

We are at the University of Cambridge, one of the world’s leading universities, and we work to its standards. Of course, we cannot fully model every possible scenario – but who better to identify the risks to humanity than us? Universities should not be ivory towers; they must address the potential consequences of their discoveries.

In 2003, you wrote that humanity’s chances of surviving the 21st century were 50 per cent. A quarter of a century later – where do we stand?

(Laughs) That figure was not meant literally. My main point was that scientific progress brings with it new dangers.

Which ones?

At the time, nuclear weapons were the obvious concern. I was among the first to alert the public to the risks of biotechnology. Natural pandemics spread more easily today because of global connectivity – the plague never reached Australia in the Middle Ages. And then there are “gain-of-function” experiments in laboratories, creating pathogens that are deadlier, more contagious, or resistant.

Do you now worry more about biotechnology than nuclear technology?

Unlike nuclear weapons, biological weapons do not require vast, hard-to-hide facilities. The equipment needed is widely available – in universities and small laboratories across the world. One single malicious actor or small group could, deliberately or through negligence, trigger catastrophe.

How can that risk be reduced?

Scientists must remain mindful of the dangers their work entails – and ensure that governments are, too. Biotechnology is underregulated. And, unlike nuclear power, there is no binding international body like the IAEA to monitor it.

What other risks are you particularly concerned about?

A growing concern is our dependence on global networks: air traffic control, power grids, the internet.

Can you name any examples?

Ninety-nine per cent of global internet traffic passes through undersea cables. Sever those – and it does not require sophisticated technology – and global communication collapses. The same is true of GPS, air traffic control and supply chains in general.

Nuclear war is regularly listed as an existential risk. Radioactive waste is rarely mentioned. Where does it stand on your list?

It is, like climate change, a slow-burn threat. But it raises an important ethical question: how much do we care about future generations? Planning deep geological repositories requires thinking in timescales of tens of thousands or even one million years. It is the only field in which we think so far ahead.

Yet as a society, our focus is increasingly short-term.

Yes, and this applies not only to radioactive waste, but also to climate change: the worst effects will only be felt in 100 or 200 years. It is hard to convey that the problem matters already today. We prefer to care for the people we know.

And this shapes politics.

Exactly. Governments generally fail to take existential risks seriously enough. The odds of such a risk materialising are low – and even lower that it will happen during a politicians’ term in office. Yet we must prepare for them because these risks are becoming more likely each year, and their consequences would be devastating.

How can we prevent this from happening?

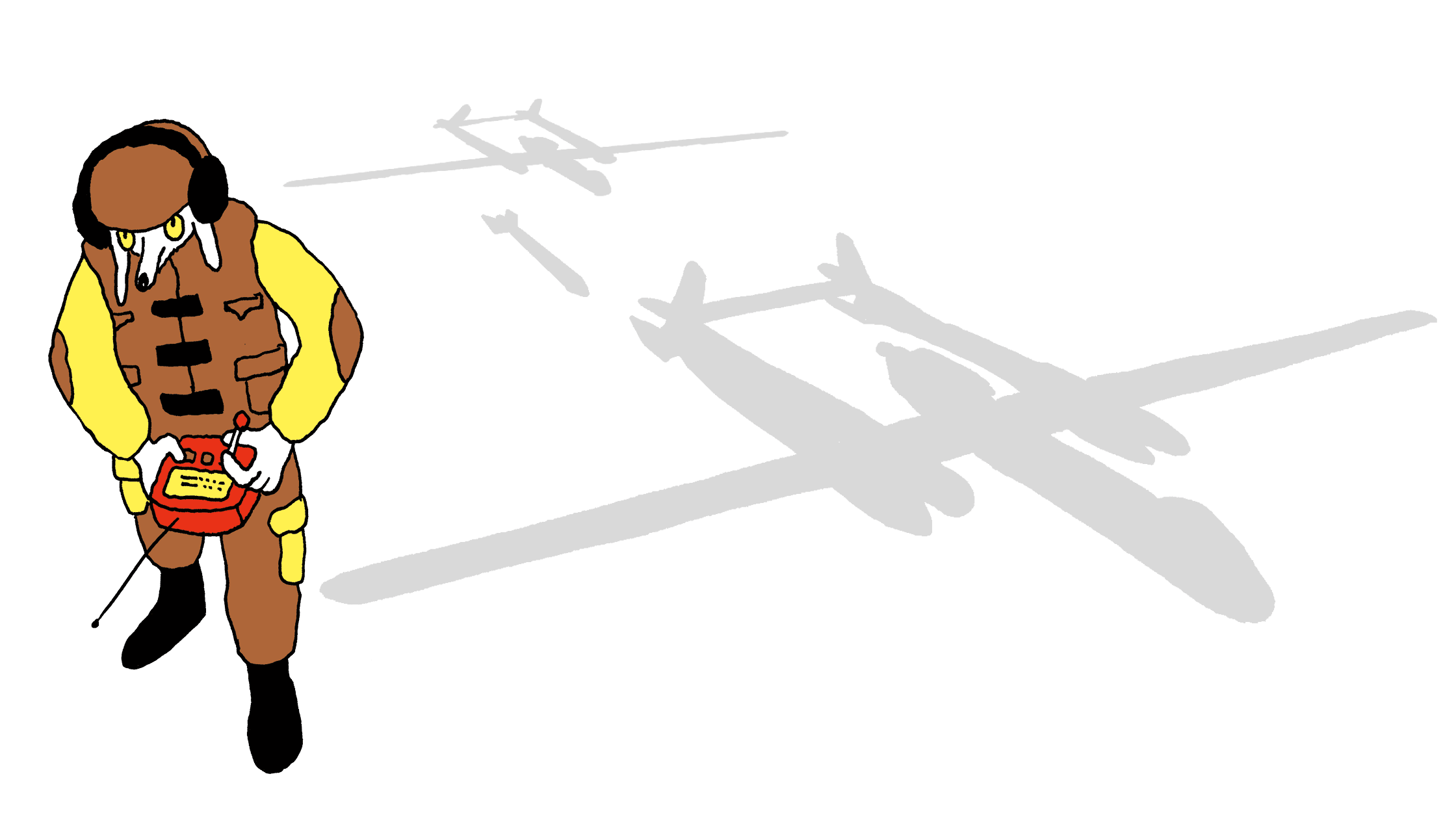

We should strive to be good ancestors. We should remind ourselves of what earlier generations did for us. We now know that the Earth will last for billions of years. The cathedral builders of the Middle Ages believed that the world would end in a few centuries – yet they built structures that would only be completed long after their deaths. Today, it is harder for us to think with a view to the long term. In just fifty years, our technology and our lives can be completely transformed.

Let us return to the here and now: so you do not see radioactive waste as a short-term threat?

In the short term, radioactive waste is unlikely to trigger a global catastrophe. The greatest risk is local radiation exposure. However, poorly secured facilities could become terrorist targets. Radioactive waste therefore remains a permanent risk – and it will not diminish in the decades ahead.

Everyone is talking about artificial intelligence. Where do you stand in this “war of belief”: will this technology save us or destroy us?

I think the hype that AI will soon become superhuman and “take control” is overblown. But I do worry about our overdependence on fragile, globally networked systems. If they fail – through malfunction or cyberattack – the global economy and social order could unravel within days. Particularly troubling is that a handful of immensely powerful companies are driving these developments. Governments must regulate and oversee them.

Can AI really be regulated? Take autonomous weapons, for instance: 192 countries might agree to a ban, but it only takes one to defect.

That is indeed a major challenge. I see an international consensus, as attempted with climate change, as the best solution. If one state opts out, there must be international pressure and the threat of sanctions. There is not much more we can do.

There is no doubt that AI will fundamentally change our daily lives in the coming decade. How should we use it?

AI has many benefits: it can analyse 30,000 X-ray images – far more than a doctor will see in a lifetime – and identify lung cancer with greater accuracy. In weather forecasting, AI can evaluate decades of cloud patterns and predict storms more precisely than traditional models. We should seize these advantages while guarding against the dangers – such as systemic collapse.

You mention it yourself: AI will transform the workplace and upend the job market.

Yes, AI will replace jobs. Fewer people will be needed in call centres and offices. That is inevitable. Rather than trying to stop this shift, we must make it socially sustainable. It is crucial that we tax AI companies and absorb those whose jobs vanish. Otherwise, not only economic upheaval but also deepening social tensions will follow.

Given these changes: what profession should young people pursue today?

Jobs that are hard to automate and that carry intrinsic meaning: medicine, teaching or law. Trades such as plumbing or gardening will also remain vital. Roles requiring direct human contact, such as elder care or social work, will hardly be replaced by AI. And, of course, we need people to supervise and scrutinise AI itself.

And what profession would you strongly advise against?

Anything based on coding.

A skill that, only ten years ago, was hailed as the future.

Yes.

Many certainties are crumbling: since 2020, we have had a pandemic, a war has returned to Europe, and now AI.

In the past, many people lived better lives in small communities – we knew our doctor, our teacher, and so on. But we must accept that change is real. It brings many conveniences, but also threatens social cohesion. What worries me especially is that today, through the internet and social media, anyone can access global communication and propaganda. That polarises societies and gives populism new fuel. But history also shows that technological surges often level off again.

How do you mean?

Aviation is a good example. Only fifty years separated the first transatlantic flight from the Boeing 747 – yet progress since has been limited. Concorde, the supersonic jet, even disappeared. This pattern shows that not everything grows exponentially.

You spend your days dealing with catastrophe scenarios, yet you smile and appear relaxed. How do you manage not to become paranoid and see doomsday everywhere?

I try to stay balanced. Many of the threats we discuss may never occur – and we can do a great deal to mitigate them. But what should not make us paranoid, but perhaps should make us depressed, is the widening gap between the world as it is and the world as it could be. What we see in Sudan, in Gaza, and elsewhere.

Some argue the world is, in fact, steadily improving.

Yes, Steven Pinker, for example, wrote a book claiming many things have improved: life expectancy, literacy, less violence. But he underestimates the new risks that threaten us – and which are often overlooked.

But statistics support Pinker.

I have debated with him publicly. To a certain extent, he is right. But Pinker believes not only that the world is improving, but that our ethics are improving, too. I strongly disagree. I see no progress in global ethics at all.

Could you elaborate?

If we look back to the cathedral builders of the Middle Ages, their lives were harsh and often miserable – but the gap between reality and possibility was small, because there was little scope for change. Today, we have the technology to give everyone a good life. That wars, inequality and blockages persist is not due to lack of means, but due to politics and economics. That is a reason enough to be depressed.

Would you call yourself risk-seeking or risk-averse?

I would say I am risk-averse. I live a comfortable, relaxed life, without craving thrills or extreme sports such as mountaineering.

Our hypothesis for this magazine is that you are in good company. The appetite for risks seems to be declining in general. We insure everything insurable, and even leisure risks are carefully calculated. Do you agree?

Yes. Of course, there are people who seek fulfilment in dangerous pursuits – but you do not need that to have led a meaningful life. On the contrary, it is a good thing today that one can live without being forced to take extreme risks. Those who find themselves in desperate situations must sometimes take dangerous paths, just like the people currently crossing the English Channel in flimsy boats.